PART 1

Fellow makers, many of us have forgotten International Women’s Day began as International Working Women’s Day. The agenda? Changing conditions for the working women of the world and uniting the working class. On March 8, 1857, garment workers in New York City marched and picketed, demanding improved working conditions, a ten hour day, and equal rights for women. On March 8, 1908, their sisters in the needle trades in New York marched again, honoring the 1857 march, demanding the vote, an end to sweatshops and regulation of child labor. In 1910 at the Second International in Copenhagen, a world wide socialist party congress, Clara Zetkin proposed March 8th be proclaimed International Working Women’s Day to honour the work and struggle of women the world over.

The garment making industry had doubled in size between 1900 and 1910 with factories cramming unskilled immigrant workers from Russia and Italy into inadequate buildings without fire escapes or working regulations. Women who had previously worked from home were now forced to work in factories as piece-work sewing shifted to assembly production to meet demand.

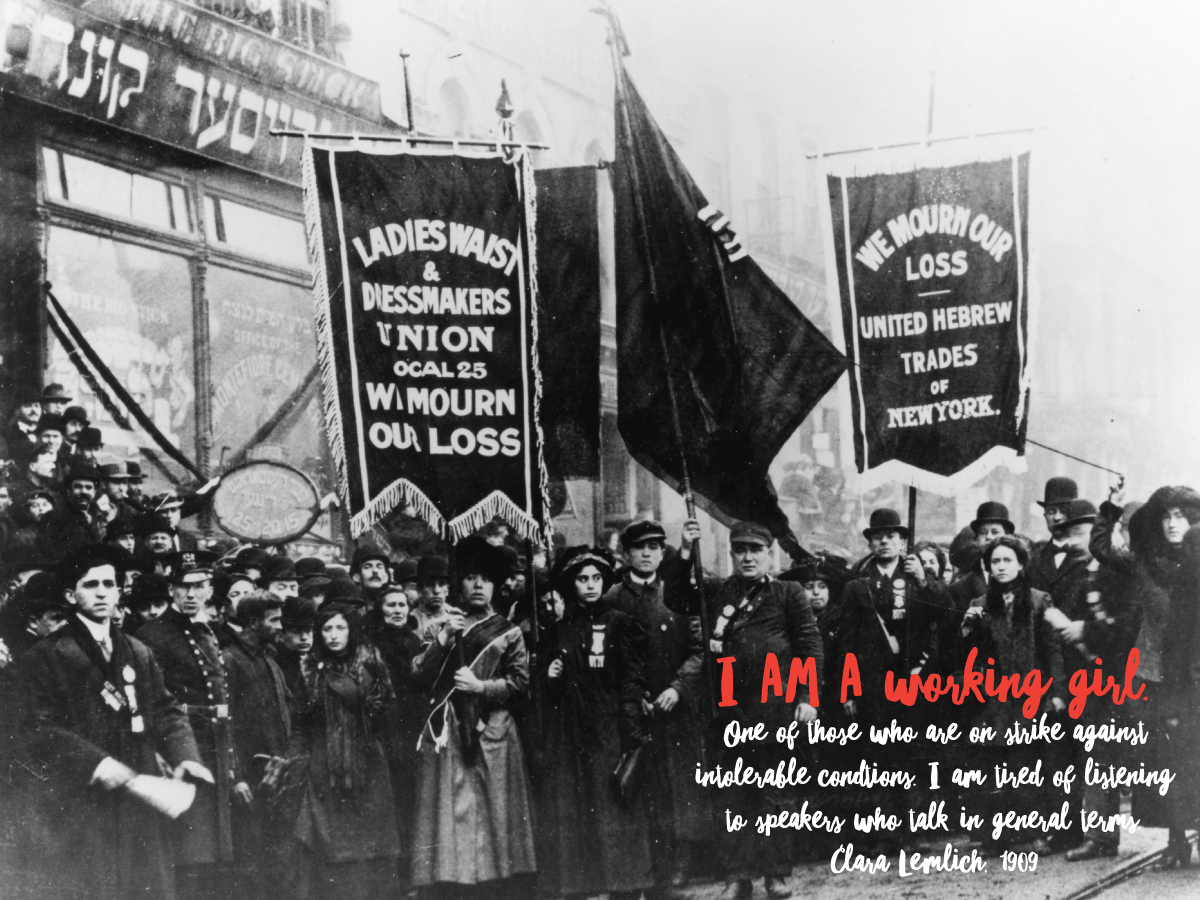

In November 1909 young women had helped instigate the “Uprising of 20,000”, the largest strike of women workers in New York history at that time, when 20,000 of New York’s 40,000 garment workers walked out of the factories and refused to work after being called to strike by Clara Lemlich. Clara was a 19 year old Ukrainian immigrant, who stood up in front of thousands of fellow workers to say “I am a working girl. One of those who are on strike against intolerable conditions. I am tired of listening to speakers who talk in general terms. What we are here for is to decide whether we shall strike or shall not strike. I offer a resolution that a general strike be declared now.” The next morning they took to the streets. After the general strike of 1909 the majority of New York shirtwaist manufacturers had signed union contracts, except for the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory and on March 25th 1911 the need for women to unite went from a revolutionary spark to a blazing fire.

March 25th, 1911

Hundreds of women filed into the ninth and tenth floors of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory as they did every morning. Some women lugged the heavy machines they would work on all day and were required to carry back and forth from the factory. Many women would also take home clothing to be worked on by the whole family, with children as young as three sewing into the night. Workers were mostly young Jewish and Italian immigrant women, who laboured long hours under miserable conditions facing regular deductions for electricity, mistakes, singing, or talking on the job. In some shops workers had to supply their own thread, needles, or rent the chairs they sat on to increase the profit margins for the shop owner. There were also men at work in the factories as pressers who spent all day standing at long tables using hot irons to press finished pieces, but the employees were overwhelmingly female.

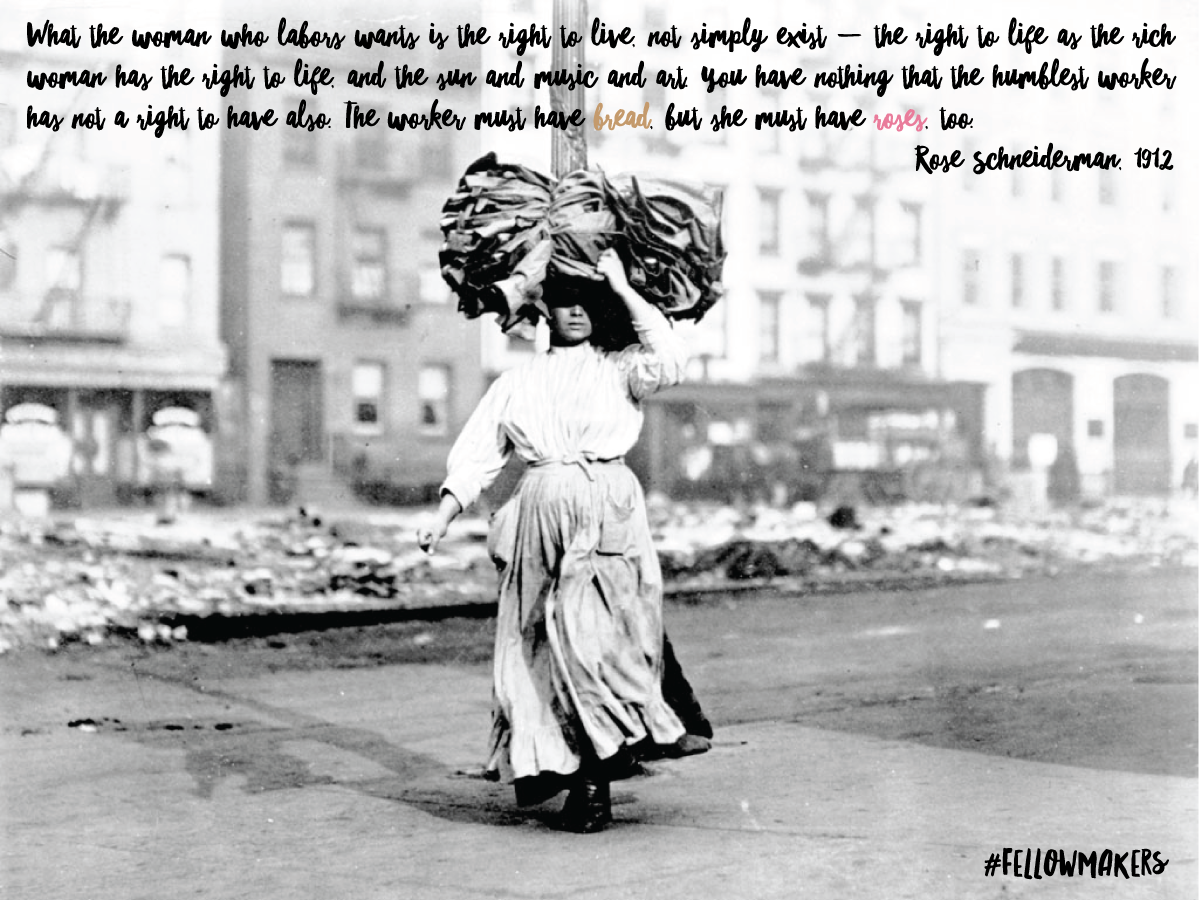

That day when the women were bent over their machines a fire broke out and ravaged the factory killing 146 people, mostly Italian or Jewish women and girls. Many leapt from the roof or windows when they could not escape the factory floor because the fire escape doors had been locked to prevent stealing. Still known as the worst factory fire in US history the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire led to sweeping marches and reforms on worker rights not only in America but around the world. The cries of workers jumping to their deaths made Frances Perkins rush out the door to watch as in under twenty minutes over a hundred lives were lost, Frances would go on to be secretary of labor under Franklin D. Roosevelt and the first woman to serve as a Cabinet secretary. The event galvanized the Progressive movement in the US by uniting wealthy women with working women to improve social conditions for all. The fire also led three young Jewish women Clara Lemlich, Rose Schneiderman, and Pauline Newman into a life of union organizing and political action. The working women who changed history were handmakers with little education or means, just like millions of us are today. Rose Schneiderman’s famous 1912 speech following the fire is as relevant now as it was then:

“What the woman who labors wants is the right to live, not simply exist — the right to life as the rich woman has the right to life, and the sun and music and art. You have nothing that the humblest worker has not a right to have also. The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too.”

We like to believe things have changed since 1911, but have they really? Now that garment and textile factories aren’t in Brooklyn but in Bangladesh we can be comfortable thinking that if we buy or make handmade we are not part of the problem. The rising rage in the handmade community around reselling, manufacturing, and ‘craft-washing’ by factories and companies obscures a much deeper issue – if handmade is to be an alternative to the sweatshops we need to learn to scale fairly, democratically, and with organized structures for advocacy and accountability. Otherwise we run the risk of not being a force for change but a self-serving way to avoid dealing with larger patterns of consumption, all while making ourselves feel good.

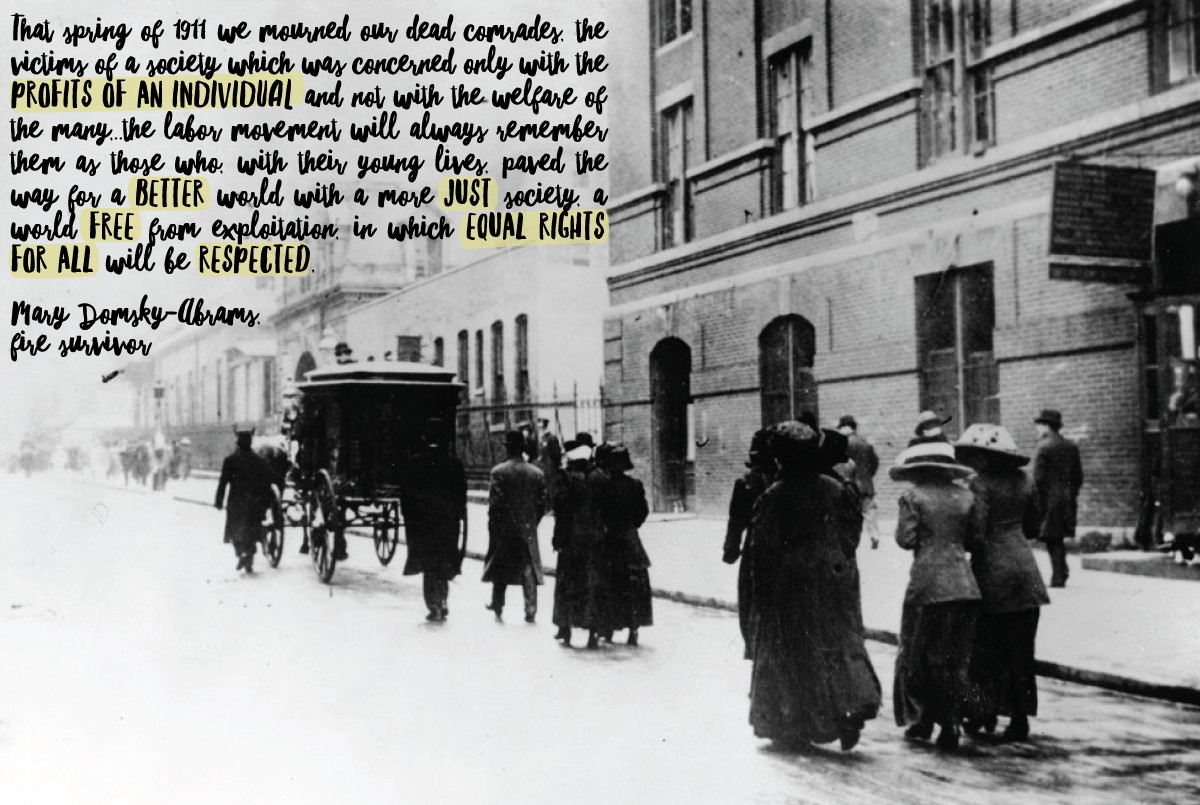

“That spring of 1911 we mourned our dead comrades, the victims of a society which was concerned only with the profits of an individual and not with the welfare of the many, of the working masses. The Triangle victims were martyrs in the fight for social justice, and the labor movement will always remember them as those who, with their young lives, paved the way for a better world with a more just society, a world free from exploitation, in which equal rights for all will be respected.” –Mary Domsky-Abrams, Blouse Operator, 9th floor (read the full interview with Leon Stein here)

Fast forward 100 years: manufacturing is carefully regulated in the developed world where we have unions, fair wage standards, building inspectors, child labour laws, and labour rights organizations. Across our borders and oceans conditions for women have not improved, they have worsened. Maybe Clara, Rose, and Pauline would have been the first to call North American sisters to arms when over 1100 people died and 2500 were injured in Bangladesh during the Rana Plaza factory collapse in 2013. Unfortunately while tragedies get major press the follow up, policy change, and worker rights get less public interest because they impact our personal luxuries or divide us politically. Major brands like Loblaws, GAP, H&M, Target, Topshop, and more, use garment manufacturers in Cambodia and Bangladesh, where the factories employ primarily women and children.

In April 2016 it will be three years since the Rana Plaza factory collapse and despite promises to take care of injured workers and improve conditions the BBC reported women like Mossammat Rebecca Khatun are unable to work, Khatun spent two days under the rubble and lost her leg along with five family members. Others like Sharmin Akter had to return to their previous jobs despite being terrified and still others are unable to find work at all. “They consider us too damaged, they think we will not be able to work as hard as we did before.” one worker is quoted as saying. As the CBC reported many of the brands implicated in the collapse have contributed little or nothing to funds that support those who were injured. In the 140 page Human Rights Watch report “Work Faster or Get Out” conditions in the Cambodian garment industry are laid bare for us to consider the price of cheap labour. 90% of garment factory workers in Cambodia are women who face being fired for pregnancy, taking bathroom breaks, or working too slowly amid many abuses of fundamental human rights. Even now locking factory doors to prevent employees from stealing or holding union meetings.

Today, a century after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire workers are still routinely dismissed, intimidated, or killed for trying to unionize to protect each other and improve conditions in countries like Cambodia, not because our countries are better than theirs but because consumers like us believe sweatshops are morally okay if things are cute. Don’t get too cozy on your handmade high horse, even shopping local or supporting ethical brands does nothing to help fellow makers in factories overseas. Sam Maher, policy director of worker safety at Labour Behind the Label wrote 18 months after the collapse, “The survivors and families of Rana Plaza have been failed by everyone. Their government, their employers, the brands and, yes, even us – the consumers. As long as our response to such tragedy is to wring our hands in guilt, to worry about our choices and how we can feel good about the clothes we buy, we will continue to fail them. As much as we may want to, we can’t shop ourselves out of this. If we really want a fashion revolution, we have to do more. We have to stand with these workers and shout as loud as we can, so that they will not be forgotten and will not be left alone.”

These are the faces of the women who are often seen as “competition” to handmade businesses – if this is our competition, what does that say about us? Photographs by Kevin Larkin for Associated Press.

Women-led movements in both the US and Canada changed how the developed world treats workers. Policies, building codes, fair wages, and employee benefits exit because workers lobbied for regulations and the right to collective bargaining. Women worked together to form trade unions, guilds, and advocacy groups even uniting housewives into unions to lobby for access to childcare and affordable rent. Yet the very concept of the working class, of worker’s/women’s rights, or unions have become dirty words so it is little wonder that International Working Women’s Day was replaced by the less polarizing International Women’s Day. Yes, all women’s lives matter, just like all lives matter but the lives of specific communities experience pressures that others with more resources do not. This is one reason why the Black Lives Matter movement is so important to the Black community, by speaking with a collective voice, intolerable conditions can change.

Despite the romance that surrounds it, entrepreneurship has led to less security for workers with many micro-business owners working well over 10 hours a day. Many also juggle parenting or second jobs to get by. Many small business owners are uninsured and injuries, pregnancies, or illness in the family can leave them reeling financially and without proper support, so it is understandable that many feel they don’t have time to work together. Despite economic instability for increasing numbers of workers, unions in North America have seen a steady decline and lack of interest from young people since general working conditions improved and the right to unionize was protected. The Freelancer’s Union and Maker’s Row in the US are working to close that gap but very little exists for handmakers globally or locally. At the same time manufacturing is a dirty word in the handmade community with so much rage directed towards any company or person who looks to grow. It can’t be chance that the main headquarters for Etsy is located just a short ride across the bridge from where the Triangle Factory fire happened, from their location in the Lower East Side where many of the Jewish immigrants lived during the time of the fire it is possible they can change commerce for the better – with our help. Of all the companies that have been built based on handmade values Etsy is leading the way in initiating many discussions around policy change, responsible manufacturing, democratic access to entrepreneurship and ethics but it is unfair to expect them to be the ‘creativity police’, makers own that role. But are we doing a good job?

Who is Responsible?

Some makers truly believe reselling or manufacturing can hurt handmade and that until we stop overseas factories all artisans will suffer, then on the other hand there are articles like this from Lucky Break Consulting on why “handmade alone isn’t enough” and is “becoming more vanilla with each passing day” justifying makers believing the only way to succeed is to pour money into programs, personal styling, and branding. This is in stark contrast to the stories in this article. The woman featured in this video who had to give up her baby to not lose her job. Or the stories featured in this Norwegian reality series where young fashion bloggers spend time living and working with Cambodian garment workers. Even though we might struggle to pay the bills from month to month, the average North American creative entrepreneur is not living or working in intolerable conditions, employers are not taking food out of our children’s mouths, and our sales usually come from niche markets who can purchase higher price points. By working together we could improve our products, photography, marketing, and values but as individual business owners we are little more than mini-corporations without any code of ethics at all. So while we argue or debate the value of handmade, fellow makers around the world struggle just to make it through the day.

No, the blame for the division of the maker movement can’t be laid on factories, platforms, or policies – the problem is the consumer – us. Many makers are incredibly privileged as Betsy Greer of Craftivism so brilliantly explains, that we have the luxury to debate what is handmade and shame other workers who don’t meet our arbitrary standards is a perfect example of this wealth and power. That the new meme for maker culture has become spoofs like this instead of knitting as a form of resistance isn’t the fault of any one company. History has proven that handmade values and the profit system don’t go well together, as Utah Phillips explains in Natural Resources on the album The Past Didn’t Go Anywhere “the profit system always follows the path of least resistance and following the path of least resistance is what made the river crooked.”

We choose to be elitist instead of organizing supports like unions or trade organization with our fellow makers. We complain about companies like Etsy instead of working with them to improve policies and support the women, who at least in Canada, represent 91% of it’s seller base according to the most recent seller survey. We shame dissenting voices when we could build an inclusive movement with a solid foundation for makers at home and around the world. Self-interest makes us mean, small-minded, and bigoted as a community leaving people more worried about sales than the people making the things we consume. If we truly care about handmade values it is time to put aside divisive arguments and work as a community to make sure that the “better world with a more just society, a world free from exploitation, in which equal rights for all will be respected” Mary wrote of after surviving the Triangle Fire finally becomes a reality and no more sisters or brothers die from “neglect of the human factor”.

Learning From History

The average North American maker feels threatened by resellers and manufacturing, we’ve come to believe handmade won’t save the world, and it sure won’t if we keep treating it like a commodity. Just buying handmade won’t change the world, but handmade values can, the belief that people, places, and process always matter more than profits and that together our hands can make a better world. These are the same values that propelled the Arts and Crafts movement in the late 1800s to 1920s when artists and craftspeople rebelled against the increased industrialization of life, the mechanization of art, the rise of factory work, and monotony of assembly line jobs. The movement gave women the chance to move crafts out of the domestic sphere and into the world of art and business where they united around creativity, made money from traditional industries and employed other women.

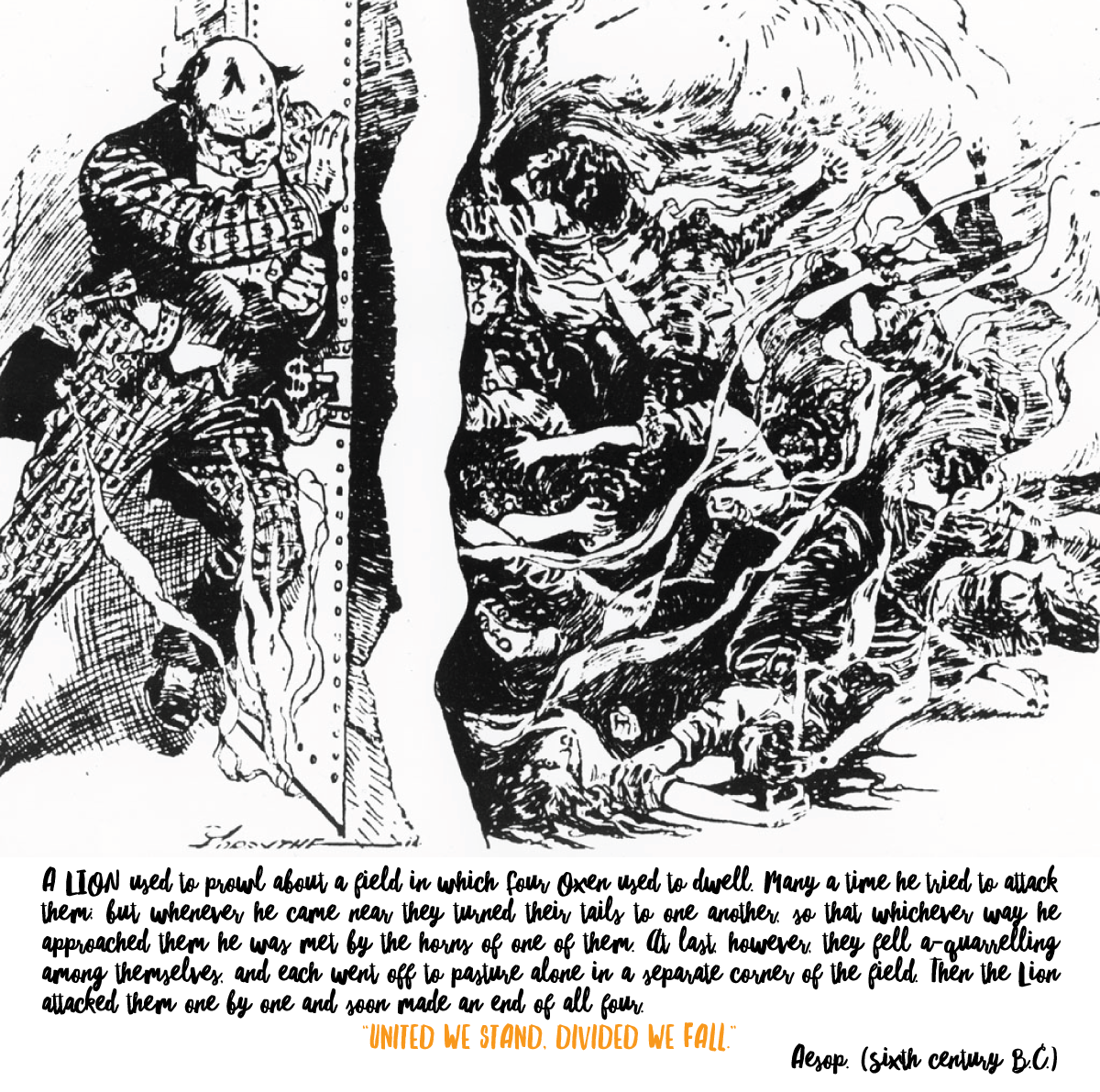

The Arts and Crafts movement in Europe and the Craftsman movement in the US led to a revival of traditional craft, the establishment of the first woman-owned potteries such as Rookwood, and influenced the future of design from Bauhaus and Modernism to some of our biggest contemporary brands like Ikea and Apple. Then, as now, what started out as a woman driven movement centred on handmade values became a marketing niche, the major players became highly branded, there were clashes between the people and the profit. The same conflicts also divided the movement with some on the side of democratic, affordable art made possible through ethical manufacturing and the other for purity of process and artisanal pretention. So what is happening now in the maker movement isn’t new, the same politics have divided us before. Is it handmade or homemade? Is it art or craft? Reducing handmade values to bourgeois elitism with primarily white folks arguing over what is craft, spurred by infighting about big business, while fellow makers and workers struggle to make do is old news. Divide and Conquer is the oldest trick in the Capitalist Handbook.

The trouble with thinking handmade can be hurt by factory made is that as artisans and crafters in the developed world with access to means, technology, and supplies we have an incredible opportunity to create ethical economies. It is our responsibility to extend the hand of fellowship to makers globally who also want to improve working conditions and wages so we can lift each other up. Factories are not our competition, the profit system is. Handmade isn’t fragile, it was here in the beginning of time when our ancestors painted pictographs and will be here to tell our stories long after all of us are dust. Handmade might not be enough to build you an empire on the backs of others but it will always enough for those who want a simple life of handmade, homemade goodness. We don’t create a culture that values craft, artistry, beauty and value by shaming or arguing – we do it by educating, investing in opportunities, and working together in solidarity within our community, our trade, and our political structures to meet our own needs and hold companies accountable. To want for each other what we want for ourselves was the foundation of the union movement and one we might want to revive if we care about handmade, women, workers, or the hands that make the world.

Makers today can learn many lessons from the Triangle Factory Fire: Factories are not the enemy, they are our responsibility; Governments don’t make policy or improve standards, they are moved by the will of the people; The factory worker/immigrant/maker are not competition, they are family; and so many more…but maybe the most important one for us to remember is the moral attributed to Aesop in the sixth century:

United we stand, divided we fall.

Sources:

- All photos except as noted via the Triangle Fire Archive, Kheel Center, Cornell University

- Arts and Crafts Movement – When Women United in Creativity, Anika Dačić, Widewalls

- 100 Years Later, the Roll of the Dead in a Factory Fire Is Complete, Joseph Berger, New York Times

- Cambodia: Garment Workers Fired for Being Pregnant

- Consumers Think Sweatshops OK if ‘Shoes Are Cute,’ Research Reveals, Neeru Paharia, Georgetown University

- Craft and Privilege Part 1, 2, & 3, Betsy Greer, Craftivism

- Do unions still matter to young people? Adam Carter, CBC News

- Etsy Manufacturing Policy

- Excerpt from Pauline Newman’s unpublished memoir, in which she recalls the beginning of the 1909 garment workers’ strike via Jewish Women’s Archive

- How long must Rana Plaza workers wait for justice?, Sam Maher, The Guardian

- If You’re Sick and Tired of Hipstery ‘Maker’ Culture, Watch This Hilarious Video Now, Adweek

- Jews of Brooklyn, edited by Ilana Abramovitch, Seán Galvin

- Knitting as Dissent: Female Resistance in America Since the Revolutionary War, Tove Hermanson, Costume Society of America, Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings

- Neglect of The Human Factor, Results of the Data Obtained by the Investigation, New York (State) Factory Investigating Commission, Preliminary Report of the Factory Investigating Commission, 1912 via the Kheel Center at Cornell University

- On Art, Labor, and Religion, edited by Ellen Gates Starr, Mary Jo Deegan, Ana-Maria Wahl

- Portraits of Rana Plaza’s Amputee Survivors, Kevin Frayer, Associated Press

- Professional Pursuits: Women and the American Arts and Crafts Movement

- Rana Plaza anniversary: Two years on, garment workers still toil in virtual slavery, Ilana Winterstein, International Business

- Sorry, Etsy. That Handmade Scarf Won’t Save the World, Emily Matchar, New York Times

- Sweatshop – Deadly Fashion

- The Cost of a Decline in Unions, Nicholas Kristof, New York Times

- The Problem With “Handmade”, Lucky Break Consulting

- Triangle Factory Fire archive, Kheel Center, Cornell University

- While She Naps Podcast Episode #57: Etsy

- “Work Faster or Get Out” Labor Rights Abuses in Cambodia’s Garment Industry, Human Rights Watch

About the author: Jessika Hepburn

Jessika is a community organizer who started developing OMHG as a gathering place for the handmade community and her fellow makers in 2010. From consulting with Etsy and advocating for diversity and inclusion, supporting new models of regional cooperation locally with Maritime Makers, to organizing community events, Jessika’s work and life revolve around the belief that when communities work together to value handmade and human goodness, anything is possible. You can find her making a life with her love of 12 years and two daughters in a little pink 200 year old house in rural Atlantic Canada filled with art and books where there is nothing she does not “know to be useful or believe to be beautiful”. Learn more about her work by visiting here.